Introduction | Life | Work | Books

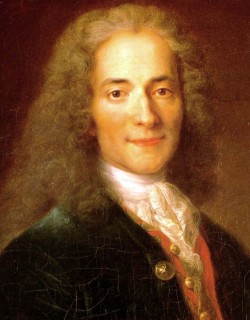

Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet)

(Portrait by Nicolas de Largillière, 1718)

|

|

Voltaire (real name François-Marie Arouet) (1694 - 1778) was a French philosopher and writer of the Age of Enlightenment. His intelligence, wit and style made him one of France's greatest writers and philosophers, despite the controversy he attracted.

He was an outspoken supporter of social reform (including the defense of civil liberties, freedom of religion and free trade), despite the strict censorship laws and harsh penalties of the period, and made use of his satirical works to criticize Catholic dogma and the French institutions of his day. Along with John Locke, Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, his works and ideas influenced important thinkers of both the American and French Revolutions.

He was a prolific writer, and produced works in almost every literary form (plays, poetry, novels, essays, historical and scientific works, over 21,000 letters and over two thousand books and pamphlets).

Voltaire was born on 21 November 1694 in Paris, France, the youngest of five children in a middle-class family. His father was François Arouet, a notary and minor treasury official; his mother was Marie Marguerite d'Aumart, from a noble family of Poitou province.

Voltaire was educated by Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris from 1704 to 1711, where he showed an early gift for languages, learning Latin and Greek as a child, and later becoming fluent in Italian, Spanish and English as well. He, however, claimed that he learned nothing but "Latin and the Stupidities".

By the time he left college, Voltaire had already decided he wanted to become a writer. However, his father very much wanted him to become a lawyer, so Voltaire pretended to work in Paris as an assistant to a lawyer, while actually spending much of his time writing satirical poetry. Even when his father found him out and sent him to study law in the provinces, he nevertheless continued to write.

Voltaire's wit soon made him popular among some of the aristocratic families of Paris and he became a favorite in society circles. When Voltaire's father obtained a job for him as a secretary to the French ambassador in the Netherlands, Voltaire fell in love with a French refugee named Catherine Olympe Dunoyer, but their scandalous elopement was foiled by Voltaire's father and he was forced to return to France.

From an early age, Voltaire had trouble with the French authorities for his energetic attacks on the government and the Catholic Church, which resulted in numerous imprisonments and exiles throughout his life. In 1717, still in his early twenties, he became involved in the Cellamare conspiracy of Giulio Alberoni against Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (then Regent for King Louis XV of France), and his writings about the Regent led to him being imprisoned in the infamous Bastille for eleven months. While there, however, he wrote his debut play, "Oedipe", whose success established his reputation. In 1718, following this incarceration, he adopted the name "Voltaire" (a complex anagrammatical play on words), both as a pen-name and for daily use, which many have seen as marking his formal separation from his family and his past.

When he offended a young nobleman, the Chevalier de Rohan, in 1726 a lettre de cachet was issued to exile Voltaire without a trial and he spent almost three years in England from 1726 to 1729. The experience greatly influenced his ideas and experiences, and he was particularly impressed by Britain's constitutional monarchy, its support of the freedoms of speech and religion, as well as the philosophy of John Locke and the scientific works of Sir Isaac Newton (1642 - 1726) on optics and gravity. After he returned to Paris, he published his views on British government, literature and religion in a collection entitled "Lettres philosophiques sur les Anglais" ("Philosophical letters on the English"), which met great controversy in France (including the burning of copies of the work), and Voltaire was again forced to leave Paris in 1734.

His second exile, from 1734 until 1749, was spent at the Château de Cirey (near Luneville in northeastern France). The Château was owned by the Marquis Florent-Claude du Châtelet and his wife, the intellectual Marquise Émilie du Châtelet (1706 - 1749), although Voltaire put some of his own money into the building's renovation. He began a fifteen year relationship with the Marquise, both as lovers and as collaborators in their intellectual pursuits, during which they collected and studied over 21,000 books and performed experiments in the natural sciences in a laboratory. He continued to write, often in collaboration with the Marquise, both fiction and scientific and historical treatises, as well as on more philosophical subjects (especially Metaphysics, the justification for the existence of God and the validity of the Bible). He renounced religion, and called for the separation of church and state and for more religious freedom. Nevertheless, he was voted into the Academie Francaise in 1746.

After the death of the Marquise in 1749 (and continuing disputes over his work "Zadig" of 1747), Voltaire moved to Potsdam (near Berlin) to join Frederick the Great (1712 - 1786), a great friend and admirer of his, with a salary of 20,000 francs a year. After a promising start, Voltaire attracted more controversy in 1753 with his attack on the president of the Berlin Academy of Science, which greatly angered Frederick. Once again, documents were burned and he fled toward Paris to avoid arrest, but Louis XV had banned him from returning to Paris, so instead he turned to Geneva, Switzerland, where he bought a large estate. Although he was welcomed at first, the law in Geneva banned theatrical performances and the publication of his works and Voltaire eventually left the city in despair.

In 1759, he finally settled at an estate called Ferney, close to the Swiss border, where he lived most of his last 20 years until just before his death, and where he continued to receive all the intellectual elite of his time. His frustrating experiences of recent years inspired his best-known work, "Candide, ou l'Optimisme" ("Candide, or Optimism") of 1759, a satire on the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and on religious and philosophical optimism in general.

Voltaire returned to a hero's welcome in Paris in 1778, at the age of 83. However, the excitement of the trip was too much for him and he died on 30 May 1778 in Paris. His last words are said to have been, "For God's sake, let me die in peace". Because of his criticism of the church, he was denied burial in church ground, although he was finally buried at an abbey in Champagne and, in 1791, his remains were moved to a resting place in the Panthéon in Paris. His heart was removed from his body and now lies in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, and his brain was also removed (although, after a series of passings-on over 100 years, it apparently disappeared after an auction).

Voltaire was a prolific writer, and produced works in almost every literary form (plays, poetry, novels, essays, historical and scientific works, over 21,000 letters and over two thousand books and pamphlets). Many of his prose works and romances were written as polemics, and were often preceded by his caustic yet conversational prefaces. "Candide" (1759), one of the best known and most successful, for example, attacked the philosophy of Gottfried Leibniz and his religious and philosophical optimism in a masterpiece of satire and irony. However, Voltaire also rejected Blaise Pascal's pessimistic philosophy of man's depravity, and tried to steer a middle course in which man was able to find moral virtue through reason.

Voltaire's largest philosophical work was the "Dictionnaire philosophique" ("Philosophical Dictionary"), published in 1764 and comprising articles contributed by him to the "Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers" ("Encyclopedia, or a systematic dictionary of the sciences, arts and crafts") (1751 - 1772) and several minor pieces. It directed criticisms at French political institutions, Voltaire's personal enemies, the Bible and the Roman Catholic Church.

He is remembered and honored in France as a courageous polemicist who indefatigably fought for civil rights (the right to a fair trial, freedom of speech and freedom of religion) and who denounced the hypocrisies and injustices of the Ancien Régime, which involved an unfair balance of power and taxes between the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobles), and the Third Estate (the commoners and middle class, who were burdened with most of the taxes). Voltaire saw the French bourgeoisie as too small and ineffective, the aristocracy as parasitic and corrupt, the commoners as ignorant and superstitious, and the church as a static force useful only to provide backing for revolutionaries.

Although he argued on intellectual grounds for the establishment of a constitutional monarchy in France, suggesting a bias towards Liberalism, he actually distrusted democracy, which he saw as propagating the idiocy of the masses. He saw an enlightened monarch or absolutist (a benevolent despotism, similar to that advocated by Plato), advised by philosophers like himself, as the only way to bring about necessary change, arguing that it was in the monarch's rational interest to improve the power and wealth of his subjects and kingdom.

Voltaire is often thought of as an atheist, although he did in fact take part in religious activities and even built a chapel at his estate at Ferney. The chief source for the misconception is a line from one of his poems (called "Epistle to the author of the book, The Three Impostors") which is usually translated as: "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him". Many commentators have argued that this is an ironical way of saying that it does not matter whether God exists or not, although others claim that it is clear from the rest of the poem that any criticism was more focused towards the actions of organized religion, rather than towards the concept of religion itself.

In fact, like many other key figures during the European Enlightenment, Voltaire considered himself a Deist, and he was instrumental in Deism's spread from England to France during his lifetime. He did not believe that absolute faith, based upon any particular or singular religious text or tradition of revelation, was needed to believe in God. He wrote, "It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason". Indeed, his focus on the idea of a universe based on reason and a respect for nature reflected the Pantheism which was increasingly popular throughout the 17th and 18th Centuries.

While not an atheist as such, he was however, opposed to organized religion. Certainly, he was highly critical of the prevailing Catholicism, and in particular he believed that the Bible was an outdated legal and/or moral reference, that it was largely metaphorical anyway (although it still taught some good lessons), and that it was a work of Man and not a divine gift, all of which gained him somewhat of a bad reputation in the Catholic Church. His attitude towards Islam varied from "a false and barbarous sect" to "a wise, severe, chaste, and humane religion". He also showed at one point an inclination towards the ideas of Hinduism and the works of Brahmin priests.

Voltaire is known for many memorable aphorisms, although they are often quoted out of context. "If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent Him", as has been mentioned, is still hotly debated as to its meaning and intentions. "All is for the best in the best of all possible worlds", from his novella "Candide", is actually a parody of the optimism of Leibniz and religion. The most often cited quotation of Voltaire is actually totally apocryphal: “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” was actually written by Evelyn Beatrice Hall in her 1906 biography of Voltaire and others, although it does capture the spirit of Voltaire’s attitude.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|

|