Introduction | Life | Work | Books

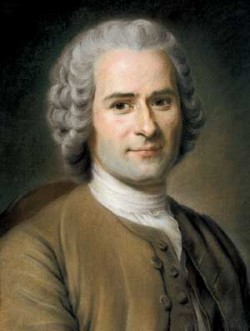

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(Pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753)

|

|

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 - 1778) was a French philosopher and writer of the Age of Enlightenment.

His Political Philosophy, particularly his formulation of social contract theory (or Contractarianism), strongly influenced the French Revolution and the development of Liberal, Conservative and Socialist theory. A brilliant, undisciplined and unconventional thinker throughout his colorful life, his views on Philosophy of Education and on religion were equally controversial but nevertheless influential.

He is considered to have invented modern autobiography and his novel "Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse" was one of the best-selling fictional works of the 18th Century (and was important to the development of Romanticism). He also made important contributions to music, both as a theorist and as a composer.

Rousseau was born on 28 June 1712 in Geneva, Switzerland (although he spent most of his life in France, he always described himself as a citizen of Geneva). His mother, Suzanne Bernard, died just nine days after his birth from birth complications. His father, Isaac Rousseau, a failed watchmaker, abandoned him in 1722 (when he was just 10 years old) to avoid imprisonment, after which time Rousseau was cared for by an uncle who sent him to study in the village of Bosey. His only sibling, an older brother, ran away from home when Rousseau was still a child.

His childhood education consisted solely of reading the Plutarch's "Lives" and Calvinist sermons in a public garden. His youthful experiences of corporal punishment at the hands of the pastor's sister developed in later life into a predilection for masochism and exhibitionism. For several years as a youth, he was apprenticed to a notary and then to an engraver.

In 1728, at the age of 16, Rousseau left Geneva for Annecy in south-eastern France, where he met Françoise-Louise de Warens, a French Catholic baroness. She later became his lover, but she also provided him with the education of a nobleman by sending him to a good Catholic school, where Rousseau became familiar with Latin and the dramatic arts, in addition to studying Aristotle. During this time he earned money through secretarial, teaching and musical jobs.

In 1742, he moved to Paris with the intention of becoming a musician and composer. He presented his new system of numbered musical notation to the Académie des Sciences but, although ingenious and compatible with typography, the system was rejected.

He was secretary to the French ambassador in Venice for 11 months from 1743 to 1744, although he was forced to flee to Paris to avoid prosecution by the Venetian Senate (he often referred to the republican government of Venice in his later political work). Back in Paris, he befriended and lived with Thérèse Levasseur, a semi-literate seamstress who bore him five children all of whom were left at the Paris orphanage soon after birth.

Towards the end of the 1740s, he became friends with the French philosopher Denis Diderot (1713 - 1784) and contributed several articles to the latter's "Encyclopédie". However, the friendship soon became strained and Diderot later described Rousseau as being "deceitful, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical and full of malice".

His 1750 "Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts" ("Discourse on the Arts and Sciences") won him first prize in an essay competition (on whether or not the development of the arts and sciences had been morally beneficial, to which Rousseau had answered in the negative) and gained him significant fame. He also continued his interest in music and his popular opera "Le Devin du Village" ("The Village Soothsayer") was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. He was outspoken in his defense of Italian music against the music of popular French composers such as Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 - 1764). In 1754, he returned to Geneva where he re-converted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship.

In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the "Discours sur l’origine et les fondments de l’inegalite" ("Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men", usually known as the "Discourse on Inequality"), which was widely read and further solidified Rousseau’s place as a significant intellectual figure. However, it also caused him to gradually become estranged from his former friends such as Diderot and the Baron von Grimm and from benefactors such as Madame d'Epinay, although he continued to enjoy the support and patronage of one of the wealthiest nobles in France, the Duc de Luxembourg. In 1761, Rousseau published the successful romantic novel "Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse" ("Julie, or The New Heloise").

In 1762, he published two major books, "Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique" ("The Social Contract, Principles of Political Right") in April and then "Émile, ou de l’Éducation (or "Émile, or On Education") in May. The books criticized religion and were banned in France and Geneva, and Rousseau was forced to flee. He made stops in Bern, Germany and in Môtiers, Switzerland, where he enjoyed for a time the protection of Frederick the Great of Prussia and his local representative, Lord Keith. However, when his house in Môtiers was stoned in 1765, he took refuge in England with the philosopher David Hume, although he soon began to experience paranoid fantasies about plots against him involving Hume and others.

He returned to the southeast of France, incognito and under a false name, in 1767. The following year, he went through a legally invalid marriage to his mistress Thérèse, and in 1770 he was finally allowed to return to Paris. One of the conditions of his return was that he was not allowed to publish any books, but after completing his "Confessions", Rousseau began private readings in 1771. He was ordered to stop by the police, and the "Confessions" was only partially published in 1782, four years after his death (all his subsequent works were only to appear posthumously).

His latter years were largely spent in deliberate withdrawal, although he continued to write, including the "Considérations sur le gouvernement de Pologne" ("Considerations on the Government of Poland"), "Rousseau: juge de Jean-Jacques" ("Rousseau: Judge of Jean-Jacques") and "Les Rêveries du promeneur solitaire" ("Reveries of the Solitary Walker"), supporting himself by copying music.

Rousseau died on 2 July 1778 of a hemorrhage while taking a morning walk on the estate of the Marquis de Giradin at Ermenonville, near Paris. Sixteen years later, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris (across from those of his contemporary, Voltaire).

Rousseau saw a fundamental divide between society and human nature and believed that man was good when in the state of nature (the state of all other animals, and the condition humankind was in before the creation of civilization), but has been corrupted by the artificiality of society and the growth of social interdependence. This idea of the natural goodness of humanity has often led to the attribution the idea of the "noble savage" to Rousseau, although he never used the expression himself and it does not adequately render his idea.

He did not, however, imply that humans in the state of nature necessarily acted morally (in fact, terms such as 'justice' or 'wickedness' are simply inapplicable to pre-political society as Rousseau understood it). For Rousseau, society's negative influence on men centers on its transformation of "amour de soi" (a positive self-love which he saw as the instinctive human desire for self-preservation, combined with the human power of reason) into "amour-propre" (a kind of artificial pride which forces man to compare himself to others, thus creating unwarranted fear and allowing men to take pleasure in the pain or weakness of others).

In "Discourse on the Arts and Sciences" (1750) Rousseau argued that the arts and sciences had not been beneficial to humankind because they were not human needs, but rather a result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they created for idleness and luxury contributed to the corruption of man, undermined the possibility of true friendship (by replacing it with jealousy, fear and suspicion), and made governments more powerful at the expense of individual liberty.

His subsequent "Discourse on Inequality" (1755) expanded on this theme and tracked the progress and degeneration of mankind from a primitive state of nature to modern society in more detail, starting from the earliest humans (solitary beings, differentiated from animals by their capacity for free will and their perfectibility, and possessed of a basic drive to care for themselves and a natural disposition to compassion or pity). Forced to associate together more closely by the pressure of population growth, man underwent a psychological transformation and came to value the good opinion of others as an essential component of their own well-being, which led to a golden age of human flourishing (with the development of agriculture, metallurgy, private property and the division of labor) but which also led to inequality.

Rousseau concluded from his analysis of inequality that the first state was invented as a kind of social contract, but a flawed one made at the suggestion of the rich and powerful to trick the general population and institute inequality as a fundamental feature of human society. In "The Social Contract" of 1762 (his most important work and one of the most influential works of Political Philosophy in the Western tradition), he offered his own alternative conception of the social contract. Opening with the dramatic lines, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. One man thinks himself the master of others, but remains more of a slave than they", Rousseau claimed (contrary to his earlier work) that the state of nature was a primitive and brutish condition, without law or morality, which humans deliberately left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation.

He argued that, by joining together into civil society through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and yet remain free, because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others, and also ensures that they themselves obey because they are (collectively) the authors of the law. It should be noted that Rousseau was bitterly opposed to the idea that the people should exercise sovereignty via a representative assembly; rather, he held that they should make the laws directly, which would effectively prevent the ideal state from becoming a large society, such as France was at the time.

Rousseau's views on religion were highly controversial. His view that man is good by nature conflicted with the doctrine of original sin, and his theology of nature (as well as the claims he made in "The Social Contract" that true followers of Jesus would not make good citizens) led to the condemnation and banning of his books in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris.

Rousseau was one of the first modern writers to seriously attack the institution of private property, and therefore is considered to some extent a forebear of modern Socialism, Marxism and Anarchism. He also questioned the assumption that the will of the majority is always correct, arguing that the goal of government should be to secure freedom, equality and justice for all within the state, regardless of the will of the majority.

Rousseau set out his influential views on Philosophy of Education in his semi-fictitious "Émile" (1762). The aim of education, he argued, is to learn how to live righteously, and this should be accomplished by following a guardian (preferably in the countryside, away from the bad habits of the city) who can guide his pupil through various contrived learning experiences. He minimized the importance of book learning and placed a special emphasis on learning by experience, and he recommended that a child's emotions should be educated before his reason. He took the subordination of women as read, however, and envisaged a very different educational process for women, who were to be educated to be governed rather than to govern.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|

|