Introduction | Life | Work | Books

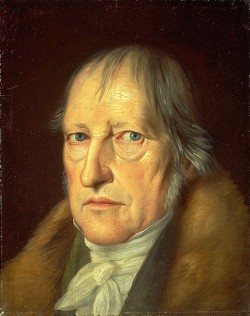

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

(Portrait by Jakob Schlesinger, 1831)

|

|

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (often known as G. W. F. Hegel or Georg Hegel) (1770 - 1831) was a German philosopher of the early Modern period. He was a leading figure in the German Idealism movement in the early 19th Century, although his ideas went far beyond earlier Kantianism, and he founded his own school of Hegelianism.

He has been called the "Aristotle of modern times", and he used his system of dialectics to explain the whole of the history of philosophy, science, art, politics and religion. Despite charges of obscurantism and "pseudo-philosophy", Hegel is often considered the summit of early 19th Century German thought.

His influence has been immense, both within philosophy and in the other sciences, and he came to have a profound impact on many future philosophical schools (whether they supported or opposed his ideas), not the least of which was the Marxism of Karl Marx which was to have so profound an effect on the political landscape of the 20th Century.

Hegel (pronounced HAY-gul) was born on 27 August 1770 in Stuttgart in south-western Germany. His father, Georg Ludwig Hegel, was secretary to the revenue office at the court of the Duke of Württemberg; his mother, Maria Magdalena Louisa (née Fromm), was the well-to-do and well-educated daughter of a lawyer at the High Court of Justice at the Württemberg court (she died when Hegel was thirteen of a "bilious fever"). Hegel had a younger sister, Christiane Luise (who was later committed to an asylum and eventually drowned herself), and a younger brother, Georg Ludwig (who was to die in Napoleon's Russian campaign of 1812).

At the age of three, Hegel went to the "German School", and entered the "Latin School" at age five, and then attended Stuttgart's Gymnasium Illustre high school from 1784 to 1788. He was a serious, hard-working and successful student, and a voracious reader from a young age, including Shakespeare, the ancient Greek philosophers, the Bible and German literature. In addition to German and Latin, he learned Greek, Hebrew, French and English.

At the age of eighteen, he entered the Tübinger Stift, a Protestant seminary attached to the University of Tübingen, where two fellow students were to become vital to his development: the poet Friedrich Hölderlin (1770 - 1843), and the younger brilliant philosopher-to-be Friedrich Schelling. The three became close friends, sharing a dislike for the restrictive environment of the seminary. Hölderlin and Friedrich Schelling soon began to be interested in the theoretical debates on Kantian philosophy, although Hegel's own critical engagement with Kant did not occur until much later (around 1800).

Having graduated from the Tübingen Seminary in 1793, Hegel became house tutor to an aristocratic family in Berne, Switzerland, and then took a similar position in Frankfurt-am-Main from 1797 to 1801. During this time he produced some early works on Christianity, and his friend Hölderlin began to exert an increasingly important influence on his thought.

In 1801, Hegel secured a position as an unsalaried lecturer at the University of Jena (with the encouragement of his old friend Schelling, who was Extraordinary Professor there). He lectured on Logic and Metaphysics and, with Schelling, gave joint lectures on an "Introduction to the Idea and Limits of True Philosophy" and held a "Philosophical Disputorium". In 1802, Schelling and Hegel founded a journal, the "Kritische Journal der Philosophie" ("Critical Journal of Philosophy"), and he produced his first real book on philosophy, "Differenz des Fichteschen und Schellingschen Systems der Philosophie" ("The Difference between Fichte's and Schelling's Systems of Philosophy") in 1801.

In 1805, the University promoted Hegel to the position of Extraordinary Professor (although still unsalaried) and, under some financial pressure, he brought out the book which introduced his system of philosophy to the world, "Phänomenologie des Geistes" ("Phenomenology of Mind"), in 1807, just after Napoleon Bonaparte (whom Hegel greatly admired) had entered the city of Jena and closed the University. The same year, he had an illegitimate son, Georg Ludwig Friedrich Fischer by his landlady, Christiana Burkhardt (who had been abandoned by her husband). However, unable to find more suitable employment, he was then forced to move from Jena and to accept a position as editor of a newspaper, the "Bamberger Zeitung", in Bamberg.

From 1808 until 1816, he was headmaster of a gymnasium in Nuremberg, where he adapted his "Phenomenology of Mind" for use in the classroom, and developed the idea of a comprehensive encyclopedia of the philosophical sciences (later published in 1817). In 1811, he married Marie Helena Susanna von Tucher, the eldest daughter of a Senator, and they had two sons, Karl Friedrich Wilhelm in 1813 and Immanuel Thomas Christian in 1814 (and, in 1817, his illegitimate son, Ludwig Fischer, who was by then orphaned, joined the Hegel household). This period saw the publication of his second major work, "Wissenschaft der Logik" ("Science of Logic") in three volumes in 1812, 1813 and 1816.

From 1816 to 1818, Hegel taught at the University of Heidelberg, and then he took an offer for the chair of philosophy at the University of Berlin, where he remained until his death in 1831. He published his "Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts" ("Elements of the Philosophy of Right") in 1821. At the height of his fame, his lectures attracted students from all over Germany and beyond, and he was appointed Rector of the University in 1830, and decorated by King Frederick William III of Prussia for his service to the Prussian state in 1831.

Hegel died in Berlin on 14 November 1831 from a cholera epidemic, and was buried in Berlin's Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, next to fellow philosophers Johann Gottlieb Fichte and Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand Solger (1780 - 1819).

Hegel published only four main books during his life: "Phänomenologie des Geistes" ("Phenomenology of Mind") in 1807, his account of the evolution of consciousness from sense-perception to absolute knowledge; the three volumes of "Wissenschaft der Logik" ("Science of Logic") in 1811, 1812 and 1816, the logical and metaphysical core of his philosophy; "Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften" ("Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences") in 1816, a summary of his entire philosophical system, intended as a textbook for a university course; and "Grundlinien der Philosophie des Rechts" ("Elements of the Philosophy of Right") in 1821, his political philosophy and his thoughts on “civil society”. A number of other works on the Philosophy of History, Philosophy of Religion, Aesthetics, and the history of philosophy were compiled from the lecture notes of his students and published posthumously.

His works have a reputation for their abstractness and difficulty (no less an academic than Bertrand Russell claimed that Hegel was the single most difficult philosopher to understand), and for the breadth of the topics they attempt to cover. These difficulties are magnified for those reading him in translation, since his philosophical language and terminology in German often do not have direct analogues in other languages (e.g. his essential term "Geist" is usually translated as "mind" or "spirit", but these still do not cover the full depth of meaning of the word).

Hegel's thought can be seen as part of a progression of philosophers (going back to Plato, Aristotle, Plotinus, Leibniz, Spinoza, Rousseau and Kant) who can generally be described as Idealists, and who regarded freedom or self-determination as real, and as having important ontological implications for soul or mind or divinity.

He developed a new form of thinking and Logic, which he called "speculative reason" (which includes the more famous concept of "dialectic") to try to overcome what he saw as the limitations of both common sense and of traditional philosophy at grasping philosophical problems and the relation between thought and reality. His method was to begin with ultra-basic concepts (like Being and Nothing), and to develop these through a long sequence of elaborations towards solutions that take the form of a series of concepts. He employed the tried-and-tested process of dialectic (which dates back to Aristotle and involves resolving a thesis and its opposing antithesis into a synthesis), but asserted that this logical process was not just a matter of form as separate from content, but had applications and repercussions in the real world. He also took the concept of the dialectic one step further, arguing that the new synthesis is not the final truth of the matter, but rather became the new thesis with its corresponding antithesis and synthesis. This process would continue effectively ad infinitum, until reaching the ultimate synthesis, which is what Hegel called the Absolute Idea.

Hegel's main philosophical project, then, was to take the contradictions and tensions he saw throughout modern philosophy, culture and society, and interpret them as part of a comprehensive, evolving, rational unity that, in different contexts, he called "the absolute idea" or "absolute knowledge". He believed that everything was interrelated and that the separation of reality into discrete parts (as all philosophers since Aristotle had done) was wrong. He advocated a kind of historically-minded Absolute Idealism (developed out of the Transcendental Idealism of Immanuel Kant), in which the universe would realize its spiritual potential through the development of human society, and in which mind and nature can be seen as two abstractions of one indivisible whole Spirit.

However, the traditional triadic dialectical interpretation of Hegel's approach (thesis - antithesis - synthesis) is perhaps too simplistic. From Hegel's point of view, analysis of any apparently simple identity or unity reveals underlying inner contradictions, and it is these contradictions that lead to the dissolution of the thing or idea in the simple form in which it presented itself, and its development into a higher-level, more complex thing or idea that more adequately incorporates the contradictions.

Hegel was the first major philosopher to regard history and the Philosophy of History as important. Hegel's Historicism is the position that all human societies (and all human activities such as science, art or philosophy) are defined by their history, and that their essence can be sought only through understanding that. According to Hegel, to understand why a person is the way he is, you must put that person in a society; and to understand that society, you must understand its history, and the forces that shaped it. He is famously quoted as claiming that "Philosophy is the history of philosophy".

His system for understanding history, and the world itself, was developed from his famous dialectic teachings of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. He saw history as a progression, always moving forward, never static, in which each successive movement emerges as a solution to the contradictions inherent in the preceding movement. He believed that every complex situation contains within itself conflicting elements, which work to destabilize the situation, leading it to break down into a new situation in which the conflicts are resolved. For example, the French Revolution constituted the introduction of real individual political freedom, but carried with it the seeds of the brutal Reign of Terror which followed, and only then was there the possibility of a constitutional state of free citizens, embodying both the benevolent organizing power of rational government and the revolutionary ideals of freedom and equality.

Thus, the history of any human endeavor not only builds upon, but also reacts against, what has gone before. This process, though, is an ongoing one, because the resulting synthesis has itself inherent contradictions which need to be resolved (so that the synthesis becomes the new thesis for another round of the dialectic). Crucially, however, Hegel believed that this dialectical process was not just random, but that it had a direction or a goal, and that goal was freedom (and our consciousness and awareness of freedom) and of the absolute knowledge of mind as the ultimate reality.

In political and social terms, Hegel saw the ultimate destination of this historical process as a conflict-free and totally rational society or state, although for Hegel this did not mean a society of dogmatic and abstract pure reason such as the French Revolution envisaged, but one which looks for what is rational within what is real and already existent. Some have argued that Hegel's vision of the state as an organic rational whole, leaves no room for individual dissent and choice, no room for the very freedom he was advocating. However, it should be noted that Hegel's idea of freedom was quite different from what we think of as the traditional Liberal conception of freedom (which he would have seen as merely the ability to follow your own caprice), and rather consists in the fulfillment of oneself as a rational individual. He did not expound in any detail, though, on his vision of the ideal state, and how such a state might avoid sinking into authoritarianism and Totalitarianism.

Hegel categorically rejected Kant's "thing-in-itself" and his noumenal world, arguing against Kant's claim that something that exists was unknowable as contradictory and inconsistent. On the contrary, he claimed that whatever is must by definition be knowable: "The real is rational, and the rational is real". He asserted that what becomes the real is "Geist" (which, as we have noted above, can be translated as mind, spirit or soul), which he also sees as developing through history, with each period having a "Zeitgeist" (spirit of the age). Thus, although individuals and whole societies change as part of the dialectical process, what is really changing is the underlying Geist. He also held that each person's individual consciousness or mind is really part of the Absolute Mind (even if the individual does not realize this), and he argued that if we understood that we were part of a greater consciousness we would not be so concerned with our individual freedom, and we would agree to act rationally in a way that did not follow our individual caprice, thereby achieving self-fulfillment.

There has been much debate about whether Hegel's philosophy should be considered religious or spiritual or not. Most have interpreted his idea of an Absolute Mind as essentially a kind of Monism, which may or may not involve a monotheistic God of the traditional Christian kind. Some have seen it as closer to a kind of Pantheism. However, most of his philosophy also makes good sense when interpreted in a non-religious way, concerned merely with human minds.

Hegel also discussed the concept of alienation in his work, the idea of something that is part of us and within us and yet seems in some way foreign or alien or hostile. He introduced the figure of the "unhappy soul", who prays to a God whom he believes to be all-powerful, all-knowing and all-good, and who sees himself in contrast as powerless, ignorant and base. Hegel submits that this is wrong because we are effectively part of God (or Geist or Mind), and thus possessed of all good qualities as well as bad.

Hegel's thought is often considered the summit of early 19th Century German Idealism. Despite the suppression (and even banning at one point) of his philosophy by the Prussian right-wing, and its firm rejection by the left-wing, Hegel's influence has been immense, both within philosophy and in the other sciences. It would come to have a profound impact on many future philosophical schools (not least those that opposed his ideas), such as Existentialism, Marxism, Nationalism, Fascism, Historicism, British Idealism and Logical Positivism and the Analytic Philosophy movement.

After his death, Hegel's followers split into two opposing camps: the Protestant, conservative Right ("Old") Hegelians, and the atheistic, revolutionary Left ("Young") Hegelians. Although that distinction is perhaps now considered somewhat naïve, it can be seen as a tribute to the breadth of Hegel's vision. In the latter half of the 20th Century, Hegel's philosophy has undergone a major renaissance, partly due to the re-evaluation of Hegel as a possible philosophical progenitor of Marxism, and partly due to a resurgence of the historical perspective that he brought to everything, and an increasing recognition of the importance of his dialectical method.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

- The Hegel Reader 1st Edition

by Stephen Houlgate (Editor)

- Hegel's Science of Logic

by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (Author), A. V. Miller (Translator)

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Phenomenology of Spirit (Cambridge Hegel Translations)

by Georg Wilhelm Fredrich Hegel (Author), Terry Pinkard (Editor), Michael Baur (Editor, Translator)

- The Philosophy of History (Dover Philosophical Classics)

by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (Author), G. W. F. Hegel (Author), J. Sibree (Translator)

- Hegel: Elements of the Philosophy of Right (Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought)

by Georg Wilhelm Fredrich Hegel (Author), Allen W. Wood (Editor), H. B. Nisbet (Translator)

- The Cambridge Companion to Hegel

by Frederick C. Beiser (Editor)

- Hegel: Texts And Commentary 1st Edition

by Walter Kaufmann (Editor, Translator)

- Hegel (Past Masters)

by Peter Singer (Author)

- Hegel and Modern Society (Modern European Philosophy)

by Charles Taylor (Author)

- Feminist Interpretations of G. W. F. Hegel (Re-Reading the Canon) 1st Edition

by Patricia Jagentowicz Mills (Editor)

- Hegel's Idea of Philosophy: With a New Translation of Hegel's Introduction to the History of Philosophy 1st Edition

by Quentin Lauer (Author), Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (Author)

- Hegel: The Great Philosophers (The Great Philosophers Series) 1st Edition

by Raymond Plant (Author)

- An Introduction to Hegel's Logic (Hackett Classics Series)

by Justus Hartnack (Author)

- Subjects of Desire Reprint Edition

by Judith Butler (Author)

- The Phenomenology of Spirit Reader: Critical and Interpretive Essays (Suny Series in Hegelian Studies) (Suny Series, Hegelian Studies) 1st Edition

by Jon Stewart (Editor)

- Philosophy Without Foundations: Rethinking Hegel (S U N Y Series in Philosophy) (SUNY SERIES IN HEGELIAN STUDIES)

by William Maker (Author)

- Hegel's Ethical Thought

by Allen W. Wood (Author)

- Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Hegel on History (Routledge Philosophy Guidebooks)

by Joseph Mccarney (Author)

- Hegel, Nietzsche, and Philosophy: Thinking Freedom (Modern European Philosophy)

by Will Dudley (Author)

- Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory

by Herbert Marcuse (Author)

- Beyond Hegel and Nietzsche: Philosophy, Culture, and Agency (Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought)

by Elliot L. Jurist (Author)

|

|