Introduction | Life | Work | Books

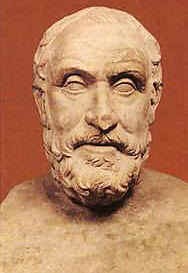

Pyrrho

|

|

Pyrrho (AKA Pyrrho of Elis) (360 - 270 B.C.) was a Greek philosopher of the Hellenistic period, from the Peloponnese Peninsula of southern Greece.

He is considered the first Skeptic and was the founder of, or at least the inspiration for, the later Greek philosophical school of Pyrrhonism, a variant of Skepticism. It is also believed that his selection of "ataraxia" (or "inner peace") as the ultimate goal of life was borrowed by Epicurus and the Epicureanism movement.

Pyrrho was born in about 360 B.C. in the small community of Elis on the Peloponnese Peninsula of southern Greece.

As a young man, Pyrrho had been a promising painter, and had pictures exhibited in the gymnasium at Elis. Later, he was diverted to philosophy through exposure to the works of Democritus. He became a disciple of Bryson of Achaea, the son of Stilpo (both from the Megarian School of philosophy which followed the doctrines of Socrates), and later a disciple of Anaxarchus of Abdera (who had been a student of Democritus).

Along with Anaxarchus, he traveled with Alexander the Great on his exploration of the East, and studied under the Gymnosophists of India and with the Magi of Persia. This exposure to Eastern Philosophy seems to have inspired him to adopt a life of solitude and, on returning to Elis, he chose to live in very poor circumstances.

Frustrated with the assertions of the Stoics and other dogmatists who claimed to possess knowledge, and overwhelmed by his inability to determine rationally which of the various competing schools of thought was correct, he founded a new school in which he taught that every object of human knowledge involves uncertainty and that it is impossible ever to arrive at the knowledge of truth.

He also acted on his own principles, prefixing all his observations with "it seems" or "it appears to me" or "perhaps". He apparently withstood bodily pain with equanimity, and showed no sign of apprehension when in danger, although the dogmatists he opposed related anecdotal stories that he carried his Skepticism to such an extreme that his friends were obliged to accompany him wherever he went so he might not be run over by carriages or fall down precipices.

He was highly honored by the Elians (who made him their chief priest and made philosophers exempt from taxation) and also by the Athenians (who conferred upon him the rights of Athenian citizenship and erected a statue and a monument in his memory).

It is believed that he lived to the ripe old age of ninety, which would put his death at around 270 B.C.

Pyrrho wrote nothing that we are aware of. His doctrines were recorded to some extent in the satiric poems (known as the "Silloi") of his pupil Timon of Phlius (c. 320 - 230 B.C.), and in the writings of Antigonus of Carystus, most of which are unfortunately lost. Today, Pyrrho's ideas are known mainly through the book "Outlines of Pyrrhonism" written by the A.D. 3rd Century Greek physician and Skeptic Sextus Empiricus. It is also through Sextus Empiricus that we have learned of a school of Skepticism known as Pyrrhonism (or Pyrrhonian Skepticism) which was founded long after Pyrrhus' death by Aenesidemus in the 1st Century B.C. Although named after Pyrrho, the relationship between the philosophy of the school and of the historical figure is murky at best.

The main principle of Pyrrho's thought can be expressed by the word "acatalepsia", which connotes the ability to withhold assent from doctrines regarding the truth of things in their own nature. He argued that we only know how things appear to us, but are ignorant of their inner substance, especially as the same thing can appear differently to different people. So, it is therefore impossible to know which opinion is right (the diversity of opinion among the wise, as well as among the vulgar, proves this). Thus, if a contradiction may be advanced against every statement with equal justification and no assertion can be known to be better than another, it is necessary to completely suspend judgment by asserting nothing definite and never making any positive statements on any subject, however trivial.

By applying these ideas of what he called "practical skepticism" to Ethics and to life in general, Pyrrho concluded that the only proper attitude is "ataraxia" (which can be translated as "inner peace" or "freedom from worry" or "apathy"), which became the ultimate goal of the early Skeptikoi. He argued that, since nothing can be known, nothing can be in itself either good or evil, and it is only opinion, custom and law which makes it appear so. If there is no good reason to prefer one course of action to another, then the absence of all activity should be the ideal of the sage. In this apathy, he will renounce all desires (which are based on the untenable opinion that one thing is better than another), and will live in undisturbed tranquillity of the soul, free from all delusions. Unhappiness is the result of not attaining what one desires (or of losing it, once attained); thus, the wise person, being free from desires, is also free from unhappiness.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|