Introduction | Life | Work| Books

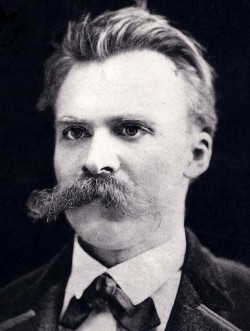

Friedrich Nietzsche

(Photograph, c. 1875)

|

|

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844 - 1900) was a 19th Century German philosopher and philologist. He is considered an important forerunner of Existentialism movement (although he does not fall neatly into any particular school), and his work has generated an extensive secondary literature within both the Continental Philosophy and Analytic Philosophy traditions of the 20th Century.

He challenged the foundations of Christianity and traditional morality, famously asserting that "God is dead", leading to (generally justified) charges of Atheism, Moral Skepticism, Relativism and Nihilism. His original notions of the "will to power" as mankind's main motivating principle, of the "Übermensch" as the goal of humanity, and of "eternal return" as a means of evaluating one's life, have all generated much debate and argument among scholars.

He wrote prolifically and profoundly for many years under conditions of ill-health and often intense physical pain, ultimately succumbing to severe mental illness. Many of his works remain controversial and open to conflicting interpretations, and his uniquely provocative and aphoristic writing style, and his non-traditional and often speculative thought processes have earned him many enemies as well as great praise. His life-affirming ideas, however, have inspired leading figures in all walks of cultural life, not just philosophy, especially in Continental Europe.

Nietzsche (pronounced NEE-cha) was born on 15 October 1844 in the small town of Röcken bei Lützen, near Leipzig in the Prussian province of Saxony (modern-day Germany). His father was Carl Ludwig Nietzsche (a Lutheran pastor and former teacher) and his mother was Franziska Oehler, and the couple had two other children, Elisabeth (born in 1846) and Ludwig Joseph (born in 1848). He was born with severe myopia and was always a delicate and sickly child.

Nietzsche's father died from a brain ailment in 1849 (when Nietzsche was only five), after more than a year of pain and suffering, and his younger brother died soon after, in 1850. These events caused Nietzsche to question why God would make good people suffer so, and were a decisive factor in his early doubts about Christianity. The family then moved to Naumburg, where they lived with Nietzsche's paternal grandmother and his two unmarried aunts. After the death of Nietzsche's grandmother in 1856, the family moved into their own house.

Nietzsche attended a boys' school and later a private school, before beginning to attend the Domgymnasium in Naumburg in 1854. Although a solitary and taciturn youth, he showed particular talents in music and language and, paradoxically, also in religious education. The internationally-recognized Schulpforta school admitted him as a pupil in 1858, and he continued his studies there until 1864, receiving an important introduction to literature (particularly that of the ancient Greeks and Romans) and a taste of life outside his early small-town Christian environment.

After graduating in 1864, Nietzsche commenced studies in theology and classical philology (the study of literary texts and linguistics) at the University of Bonn, ostensibly with a view to following his father into the priesthood. After just one semester, though, (much to the dismay of his mother), he stopped his theological studies and announced that he had lost his faith (although, two years earlier, he had already argued that historical research had discredited the central teachings of Christianity). Nietzsche then concentrated on philology under Professor Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl (1806 - 1876), whom he followed to the University of Leipzig the next year, producing his first philological publications soon thereafter.

In 1865, Nietzsche thoroughly studied the works of Arthur Schopenhauer and, in 1866, he read Friedrich Albert Lange's "Geschichte des Materialismus" ("History of Materialism"). These works, as well as Europe's increasing concern with science, Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, and the general rebellion against tradition and authority greatly intrigued Nietzsche, and he looked to expand his horizons beyond philology and to study more philosophy.

After his one year of voluntary service with the Prussian army was curtailed by a bad riding accident in March 1868, he returned to his studies and graduated later in 1868. Although he was considering giving up philology for science at that time, he nevertheless accepted an offer to become professor of classical philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland. He renounced his Prussian citizenship, and remained officially stateless thereafter. Although he did serve in the Prussian forces during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 to 1871 as a medical orderly (witnessing there something of the horrors of war, as well as contracting diphtheria and dysentery), he observed the establishment of the German Empire and the militaristic era of Otto von Bismarck as a skeptical outsider.

During his time at Basel, Nietzsche frequently visited Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima, and was accepted into their inner circle. Wagner was a strong believer in Schopenhauer's theory that great art was the only way to overcome the misery inherent in human existence, and he became something of a surrogate father to Nietzsche. In 1872, he published his first book, "The Birth of Tragedy out of the Spirit of Music", a profoundly pessimistic work in the style of Schopenhauer and Wagner, in which he asserted among other things that the best thing was not to have been born and the second best thing was to die young. His one-time teacher and mentor, Professor Ritschl, however, berated its lack of philological rigor. Gradually, from 1876 onwards, his increasing friendship with Paul Rée influenced him in dismissing the pessimism of his early writings, and he soon broke definitively with Wagner, whose growing Nationalism nauseated Nietzsche.

He pursued his own individualistic philosophy and, in 1878, published the controversial and isolating "Menschliches, Allzumenschliches" ("Human, All Too Human"). In 1879, hopelessly out of touch with his colleagues at the University of Basel and after a significant decline in health which forced him to take longer and longer holidays until regular work became impractical, Nietzsche had to resign his position at Basel. His health had always been precarious, with moments of acute shortsightedness, migraine headaches and violent stomach upsets, possibly as a result of syphilis contracted in a brothel as a student. In search of a palliative for his delicate health, he traveled frequently over the next ten years, living (on his pension from Basel, but also on aid from friends) as an independent author near St. Moritz in Switzerland, in the Italian cities of Genoa, Rapallo and Turin, and in the French city of Nice. Between 1881 and 1888, he returned repeatedly to a sparsely-furnished rented room in Sils Maria in the Swiss Alps, where he wrote some of his most important work, writing until noon and then walking in the mountains in the afternoon. He occasionally returned to Naumburg to visit his family, and his past students, Peter Gast (AKA Heinrich Köselitz: 1854 - 1918) and Franz Overbeck (1837 - 1905), who remained consistently faithful friends.

This, then, marked Nietzsche's most productive period and, starting with 1878's "Menschliches, Allzumenschliches", he would publish one book (or major section of a book) each year until 1888, his last year of writing. He had little or no luck with romantic relationships, many women apparently put off by his huge mustache. In 1882, as well as publishing the first part of "Die fröhliche Wissenschaft" ("The Gay Science"), he met Lou Andreas Salomé (1861 - 1937), a gifted student and friend of Wagner, Freud and Rilke among others. They traveled together around Italy, together with his great friend Paul Rée, but Nietzsche's spirits were severely dampened when she refused his offer of marriage.

In the face of renewed fits of illness, in near isolation after a falling-out with his mother and sister regarding Salomé, and plagued by suicidal thoughts, Nietzsche fled to Rapallo, where he wrote the first part of "Also sprach Zarathustra" ("Thus Spoke Zarathustra") in just ten days. The book was published in four parts between 1883 and 1885, but the market received it only to the degree required by politeness and the book remained largely unsold. The poor reception of the new alienating style and atheistic content of "Zarathustra" increased his isolation and made him effectively unemployable at any German University. He nursed feelings of revenge and resentment, and broke with his anti-Semitic German editor, Ernst Schmeitzner, printing "Jenseits von Gut und Böse" ("Beyond Good and Evil") at his own expense in 1886, despite a severe shortage of funds.

Very slowly, his work attracted more interest, but he continued to have frequent and painful attacks of illness, which made prolonged work impossible. Georg Brandes, who had started to teach the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard in the 1870s, delivered one of the first lectures on Nietzsche's philosophy in the late 1880s. In 1887, he published "Zur Genealogie der Moral" ("On the Genealogy of Morality") , considered by many academics to be his most important work. "Götzen-Dämmerung" ("Twilight of the Idols") and "Der Antichrist" ("The Antichrist") were both written in 1888, and his health and his spirits seemed to improve somewhat. Late in 1888, he penned his autobiographical and eccentrically self-laudatory "Ecce Homo".

However, in Turin, early in 1889, Nietzsche first exhibited apparent signs of mental illness. He sent bizarre short writings, known as the "Wahnbriefe" (or "Madness Letters") to various friends, in which he claimed to be Jesus, Napoleon, Dionysus, Buddha and Alexander the Great among others, and saw himself almost as a God figure taking on the suffering of all mankind. Eventually, his old friend Overbeck traveled to Turin and brought Nietzsche back to a psychiatric clinic in Basel. Now, fully in the grip of insanity (variously attributed to syphilis, brain cancer and frontotemporal dementia), he was transferred to a clinic in Jena where he was looked after by his mother and sister, and where various unsuccessful attempts at a cure were made, until his mother finally took him back to her home in Naumburg.

Ironically, Nietzsche's reception and recognition enjoyed their first surge during this period, as Overbeck and Gast published some of his still unpublished work (although they withheld "The Antichrist" and "Ecce Homo" due to their more radical content). During the late 19th Century, Nietzsche's ideas were commonly associated with anarchist movements and appear to have had influence within them, particularly in France and the United States. He had some following among left-wing Germans in the 1890s; German conservatives, however, wanted to ban his work as subversive.

After the death of his mother in 1897, Nietzsche lived in Weimar, where his sister Elisabeth cared for him. Many people, including Rudolf Steiner (1861 - 1925), came to visit him, but he remained uncommunicative. In 1898 and 1899, he suffered from at least two strokes which partially paralyzed him and left him unable to speak or walk and, after another stroke the next year, combined with pneumonia, he died on August 25 1900. He was buried beside his father at the church in Röcken.

Nietzsche's books tend to be more self-consciously literary than those of most philosophers, and often read more like novels than like closely-argued philosophical treatises. The philosophy within them, therefore, often needs to be "teased out", leaving them open to a variety of interpretations (a notorious and perennial problem with Nietzsche's work).

He also wrote in a uniquely provocative style (he called himself a "philosopher of the hammer"), and he frequently delivered trenchant critiques of Christianity and of great philosophers like Plato and Kant in the most offensive and blasphemous terms possible (given the context of 19th Century Europe). His arguments often employed ad-hominem (or personal) attacks and emotional appeals, and he tended to jump from one grand assertion to another with little sustained logical support or elucidation of the connection between his ideas. All these aspects of Nietzsche's style ran counter to traditional values in philosophical writing, and they alienated Nietzsche from the academic establishment both in his time and, to a lesser extent, today, when he is still often dismissed as inconsistent and speculative.

Many of his works remain controversial, and the meanings and relative significance of some of his key concepts remain contested. His distinctive German language style, his fondness for aphorism and the distance he maintained from the major existing schools of philosophy, have led to his subsequent adoption by many and varied political movements on both the right and the left. The political dictators of the 20th Century, including Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini, all read Nietzsche, and the Nazis made (admittedly selective) use of Nietzsche's philosophy, an association which caused Nietzsche's reputation to suffer after World War II.

Unusually for a major philosopher, his influences were as much non-philosophical as philosophical, including the philologist Friedrich Wilhelm Ritschl (1806 - 1876), the Swiss art historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818 -1897), the Russian novelists Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821 - 1881) and Leo Tolstoy (1828 - 1910), the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821 - 1867), the composer Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883) and the naturalist Charles Darwin (1809 - 1882). The influences of philosophers such as Plato, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill and Arthur Schopenhauer, while perhaps important, were almost totally negative. Nevertheless, Nietzsche's ideas themselves exercised a major influence on several prominent European philosophers, including Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze (1925 - 1995), Jacques Derrida, Martin Heidegger, Albert Camus (1913 - 1960), and Jean-Paul Sartre, as well as on leading figures in other walks of cultural life.

His most important books include "Menschliches, Allzumenschliches" ("Human, All Too Human") of 1878, "Die fröhliche Wissenschaft" ("The Gay Science") of 1882, "Also sprach Zarathustra" ("Thus Spoke Zarathustra") of 1883 - 1885, "Jenseits von Gut und Böse" ("Beyond Good and Evil") of 1886, "Zur Genealogie der Moral" ("On the Genealogy of Morality") of 1887, and "Götzen-Dämmerung" ("Twilight of the Idols") and "Der Antichrist" ("The Antichrist"), both of 1888. It is in these books that Nietzsche develops some of his major themes (which are discussed in more detail below), including his "immoralism", his view that "God is dead", his notions of the "will to power" and of the "Übermensch", and his suggestion of "eternal return".

In Ethics, Nietzsche called himself an "immoralist" and harshly criticized the prominent moral schemes of his day, including Christianity, Kantianism and Utilitarianism. However, rather than destroying morality, Nietzsche wanted a re-evaluation of the values of Judeo-Christianity, preferring the more naturalistic source of value which he found in the vital impulses of life itself. In his "Beyond Good and Evil" in particular he argued that we must go beyond the simplistic Christian idea of Good and Evil in our consideration of morality. Nietzsche saw the prevailing Christian system of faith as not only incorrect but as harmful to society, because it effectively allowed the weak to rule the strong, stifled artistic creativity, and, critically, suppressed the "will to power" which he saw as the driving force of human character. He had an ingrained distrust of overarching and indiscriminate rules, and strongly believed that individual people were entitled to individual kinds of behavior and access to individual areas of knowledge.

In the absence of God, then, all values, truths and standards must be created by us rather than merely handed to us by some outside agency, which Nietzsche (and the Existentialists who later embraced this idea) as a tremendously empowering, even if not a comforting, thing. His solution to the vacuum left by the absence of religion was essentially to "be yourself", to be true to oneself, to be uninhibited, to live life to the full, and to have the strength of mind to carry through one's own project, regardless of any obstacles or concerns for other people, the weak, etc. This was his major premise, and also the goal towards which he thought all Ethics should be directed.

However, it was not only the values of Christianity that Nietzsche rebelled against. He was also critical of the tradition of secular morality; the "herd values", as he called them, of the everyday masses of humanity; and at least some of the traditions deriving from Ancient Greece, principally those of Socrates and Plato.

He posited that the original system of morality was the "master-morality", dating back to ancient Greece, where value arises as a contrast between good (the sort of traits found in a Homeric hero: wealth, strength, health and power) and bad (the sort of traits conventionally associated with slaves in ancient times: poor, weak, sick, and pathetic). "Slave-morality", in contrast, came about as a reaction to master-morality, and is associated with the Jewish and Christian traditions, where value emerges from the contrast between good (associated with charity, piety, restraint, meekness and subservience) and evil (associated with cruelty, selfishness, wealth, indulgence and aggressiveness). Initially a ploy among the Jews and Christians dominated by Rome to overturn the values of their masters, to justify their situation and to gain power for themselves, Nietzsche saw the slave-morality as a hypocritical social illness that has overtaken Europe, which can only work by condemning others as evil, and he called on the strong of the world to break their self-imposed chains and assert their own power, health and vitality on the world.

The famous statement "God is dead" occurs in several of Nietzsche's works (notably in "The Gay Science" of 1882), and has led most commentators to regard Nietzsche as an Atheist. He argued that modern science and the increasing secularization of European society had effectively "killed" the Christian God, who had served as the basis for meaning and value in the West for more than thousand years. He claimed that this would eventually lead to the loss of any universal perspective on things and any coherent sense of objective truth, leaving only our own multiple, diverse and fluid perspectives, a view known as Perspectivism, a type of Epistemological Relativism. (Among his other well-known quotes of a relativistic nature are: "There are no facts, only interpretations" and "There are no eternal facts, as there are no absolute truths"). However, some commentators have noted that the death of God may lead beyond bare Perspectivism to outright Nihilism, the belief that nothing has any importance and that life lacks purpose, and even Nietzsche himself was concerned that the death of God would leave a void where certainties once existed.

At the heart of many of Nietzsche's ideas lies his belief that in order to achieve anything worthwhile, whether it be scaling a mountain to take in the views or living a good life, hardship and effort are necessary. He went so far as to wish on everyone he cared about a life of suffering, sickness and serious reversals in life, so that they could experience the advantage of overcoming such setbacks. His was the original "no pain, no gain" philosophy, and he believed that in order to harvest great happiness in life, it was necessary to live dangerously and take risks. For Nietzsche, therefore, sorrows and troubles were not to be denied or escaped (he particularly despised people who turned to drink or to religion), but to be welcomed and cultivated and thereby turned to one's advantage. This is exemplified by a famous quote from his book "Ecce Homo": "what does not kill me, makes me stronger".

An important element of Nietzsche's philosophical outlook is the concept of the "will to power", which provides a basis for understanding motivation in human behavior. His notion of the will to power can be viewed as a direct response and challenge to Schopenhauer's "will to live". Schopenhauer regarded the entire universe and everything in it as driven by a primordial will to live, resulting in the desire of all creatures to avoid death and to procreate. He also saw this as the source of all evil and unhappiness in the world. Nietzsche, on the other hand, appeals to many instances in which people and animals willingly risk their lives in order to promote their power (most notably in instances like competitive fighting and warfare). He suggested that the struggle to survive is a secondary drive in the evolution of animals and humans, less important than the desire to expand one’s power. He even went so far as to posit matter itself as a center of the will to power. In Nietzsche's view, again in direct opposition to Schopenhauer, the will to power was very much a source of strength and a positive thing.

He contrasted his theory with several of the other popular psychological views of his day, such as Utilitarianism (which claims that all people want fundamentally to be happy, an idea Nietzsche merely laughed at) and Platonism (which claims that people ultimately want to achieve unity with the good or, in Christian Neo-Platonism, with God). In each case, Nietzsche argued that the "will to power" provides a more useful and general explanation of human behavior.

Another concept important to an understanding of Nietzsche's thought is that of the "Übermensch", introduced in his 1883 book "Also sprach Zarathustra" ("Thus Spoke Zarathustra"). Variously translated as "superman", "superhuman" or "overman" (although the word is actually gender-neutral in German), this refers to the person who lives above and beyond pleasure and suffering, treating both circumstances equally, because joy and suffering are, in his view, inseparable. The Übermensch is the person who lives life to the full according to his own values, a free spirit, uninhibited and confident, although exhibiting an underlying generosity of spirit, and avoiding instinctively all those values which Nietzsche considered negative. Perhaps a better translation of Übermensch, in some ways, is that of "overcoming", which better describes the idea of mankind seeking a new way ahead in total freedom and without the need for God, and also reflects the need Nietzsche saw for conquering and overcoming all that is comfortable, unadventurous and cowardly within oneself.

Nietzsche saw this as a goal for all of humanity to set for itself, and its relation to later Nazi interpretations and eugenics is highly debatable. The idea of the Übermensch was to some extent co-opted by the Nazi regime, largely based on a re-edited version of some of Nietzsche's later works by his sister Elisabeth to promote German Fascist ideology and Aryan ideals, although this is generally held to be a gross (and probably deliberate) misinterpretation of a man who abhorred all forms of Nationalism and always promoted individualism.

Likewise, his notion of "eternal return" (or "eternal recurrence") has generated much argument among scholars. Nietzsche suggested that if a person could imagine their life repeating over and over again for all eternity, each moment recurring in exactly the same way, then those who could embrace the idea cheerfully are, ipso facto, leading the right sort of life, and those who recoil with horror from this idea have not yet learned to love and value life sufficiently. Nietzsche is almost certainly not proposing that this is literally the way the real world works (as some have suggested), but he is using it as a kind of metaphor to show how we should judge our moral conduct. Some scholars (particularly the later Existentialists) have interpreted the idea as a perpetually recurring condition of human existence, as one faces, in every moment, infinite possibilities or modes of interpretation.

Another idea which Nietzsche came back to several times in his works, beginning with his very first book "The Birth of Tragedy", is that the best, and perhaps the only, way in which life can be justified is as an aesthetic phenomenon. His point was that, if there is nothing outside this world (no God, no transcendental realm of any sort), then any justification or meaning that life has must be derived from within itself, in the same way as the meaning of a painting or a poem comes only from within itself. In fact, he comes close to suggesting that maybe life itself is just a great cosmic drama, similar to Shakespeare's notion that "all the world's a stage".

Until the last years of his life, Nietzsche made no attempt to build a system of any kind. However, his final project, begun in his last books, "Twilight of the Idols", "The Antichrist" and "Ecce Homo", was to be nothing less than what he called the "re-valuation (or trans-valuation) of all values", a prescription for morality in a post-God world and a path towards the realization of man as his own God. This was to be Nietzsche's attempt to draw all his main themes together into a single comprehensive work, tentatively entitled "The Will To Power". But by this time his intellectual abilities were severely disrupted by his illness, and he was not able to continue and complete the works.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

- Nietzsche's Werke (Classic Reprint) (German Edition) (German) Paperback– January 4, 2018

by Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (Author)

- Basic Writings of Nietzsche (Modern Library Classics) Paperback – November 28, 2000

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), Peter Gay (Introduction), Walter Kaufmann (Translator)

- A Nietzsche Reader (Penguin Classics) Paperback – October 26, 1978

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), R. J. Hollingdale (Translator, Introduction)

- Nietzsche: Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future (Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy) 1st Edition

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), Rolf-Peter Horstmann (Editor), Judith Norman (Translator)

- Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is; Revised Edition (Penguin Classics) Paperback – December 1, 1992

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), R. J. Hollingdale (Translator), Michael Tanner (Introduction)

- Thus spoke Zarathustra: A book for everyone and no one

by Friedrich Nietzsche, Translated and introduction by R.J. Hollingdale Nietzsche (Author)

- Twilight of the Idols: or How to Philosophize with a Hammer (Oxford World's Classics) Reissue Edition

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), Duncan Large (Translator)

- The Will to Power New Ed Edition

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), Walter Kaufmann (Editor, Translator), R. J. Hollingdale (Translator)

- Nietzsche: The Gay Science: With a Prelude in German Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs (Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy) New Ed Edition

by Friedrich Nietzsche (Author), Bernard Williams (Editor), Josefine Nauckhoff (Translator), Adrian Del Caro (Translator)

- The Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche (Cambridge Companions to Philosophy) Paperback – March 7, 1996

by Bernd Magnus (Editor), Kathleen Higgins (Editor)

- Zarathustra's Secret Hardcover – June, 2002

by Joachim Kohler (Author), Joachirn Köhler (Author), Ronald Taylor (Translator)

- Nietzsche: A Very Short Introduction Paperback – February 1, 2001

by Michael Tanner (Author)

- Nietzsche: The Man and his Philosophy by R. J. Hollingdale (1999-04-28) Hardcover – 1656

by R. J. Hollingdale

- Feminist Interpretations of Friedrich Nietzsche (Re-Reading the Canon) 1st Edition

by Kelly Oliver (Editor), Marilyn Pearsall (Editor)

- Nietzsche: The Great Philosophers (The Great Philosophers Series) 1st Edition

by Ronald Hayman (Author)

- Nietzsche (Arguments of the Philosophers) 1st Edition

by Richard Schacht (Author), Ted Honderich (Editor)

- New Nietzsche: Contemporary Styles of Interpretation 1st Edition

by David Allison (Editor)

- What Nietzsche Really Said by Kathleen M. Higgins (2000-02-22)Hardcover – 1673

by Kathleen M. Higgins;Robert C. Solomon (Author)

- The Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Nietzsche On Morality (Routledge Philosophy GuideBooks)1st Edition

by Brian Leiter (Author)

- Hegel, Nietzsche, and Philosophy: Thinking Freedom (Modern European Philosophy) by Will Dudley (2002-09-16) Hardcover – 1726

by Will Dudley (Author)

- Beyond Hegel and Nietzsche: Philosophy, Culture, and Agency (Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought) Paperback – February 7, 2002

by Elliot L. Jurist (Author)

- Nietzsche, Biology and Metaphor by Gregory Moore (2002-02-11)Hardcover – 1734

by Gregory Moore (Author)

- The Invention of Dionysus 1st Edition

by James I. Porter (Author)

- Nietzsche as Philosopher (Columbia Classics in Philosophy) (Paperback) - Common Paperback – 2005

by By (author) Arthur Coleman Danto (Author)

|

|