Introduction | Life | Work| Books

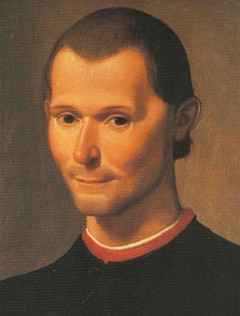

Niccolò Machiavelli

(Detail from a portrait by Santi di Tito, late 16th Century)

|

|

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (1469 - 1527) was an Italian philosopher, political theorist, diplomat, musician and writer of the Renaissance period. He was a central figure in the political scene of the Italian Renaissance, a tumultuous period of plots, wars between city states and constantly shifting alliances.

Although he never considered himself a philosopher (and often overtly rejected philosophical inquiry as irrelevant), many subsequent political philosophers have been influenced by his ideas. His name has since passed into common usage to refer to any political move that is devious or cunning in nature, although this probably represents a more extreme view than Machiavelli actually took.

He is best known today for two main works, the well-known "The Prince" (a treatise on political realism and a guide on how a ruler can retain control over his subjects), and the "Discourses on Livy" (the most important work on republicanism in the early modern period).

Although he is sometimes presented as a model of Moral Nihilism, that is actually highly questionable as he was largely silent on moral matters and, if anything, he presented an alternative to the ethical theories of his day, rather than an all-out rejection of all morality. He was also accused of Atheism, again with little justification.

Machiavelli was born in Florence, Italy on 3 May 1469, the second son of Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli (a lawyer) and Bartolommea di Stefano Nelli. His family were believed to be descended from the old marquesses of Tuscany, and were probably quite wealthy.

Little is known of his early life, but his education (possibly at the University of Florence) left him with a thorough knowledge of the Latin and Italian classics, and he was trained as a man with great nobility and severe rigor by his father. He entered governmental service in Florence as a clerk and ambassador in 1494, the same year as Florence had restored the republic and expelled the ruling Medici family. He was soon promoted to Second Chancellor of the Republic of Florence, with responsibility for diplomatic negotiations and military matters. Between 1499 and 1512, he undertook a number of diplomatic missions to the court of Louis XII of France, Ferdinand II of Aragón and the Papacy in Rome. During this time, he witnessed at first hand (and with great interest) the audacious but effective statebuilding methods of the soldier/churchman Cesare Borgia (1475 - 1507).

From 1503 to 1506, Machiavelli was responsible for the Florentine militia and the defense of the city (he distrusted mercenaries, preferring a citizen militia). He had some early success, but in 1512, the Medici (with the help of Pope Julius II and Spanish troops) defeated the Florentine force, and Machiavelli was removed from office, accused of conspiracy and arrested. After torture, he was eventually released and retired to his estate at Sant'Andrea (in Percussina near Florence) and began writing the treatises that would ensure his place in the history of Political Philosophy, "Il Principe" ("The Prince") and "Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio" ("Discourses on Livy").

Near the end of his life, and probably with the aid of well-connected friends whom he had been constantly badgering, Machiavelli began to return to the favor of the Medici family. From 1520 to 1525, he worked on a "History of Florence", commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de'Medici (who later become Pope Clement VII). However, before he could achieve a full rehabilitation, he died in San Casciano, just outside of Florence, on 21 June 1527. His resting place is unknown.

Machiavelli's best known work, "Il Principe" ("The Prince"), was written in some haste in 1513 while in exile on his farm outside Florence, and was dedicated to Lorenzo de'Medici in the hope of regaining his status in the Florentine Government. However, it was only formally published posthumously in 1532. In it, he described the arts by which a Prince (or ruler) could retain control of his realm. A "new" prince has a much more difficult task than a hereditary prince, since he must stabilize his newfound power and build a structure that will endure, a task that requires the Prince to be publicly above reproach but privately may require him to do immoral things in order to achieve his goals. He outlined his criteria for acceptable cruel actions and pointed out the irony in the fact that good can come from evil actions.

Although "The Prince" did not dispense entirely with morality nor advocate wholesale selfishness or degeneracy, the Catholic Church nevertheless put the work on its index of prohibited books, and it was viewed very negatively by many Humanists, such as Erasmus. It marked a fundamental break between Realism and Idealism. Although never directly stated in the book, "the end justifies the means" is often quoted as indicative of the Pragmatism or Instrumentalism that underlies Machiavelli's philosophy. He also touched on totalitarian themes, arguing that the state is merely an instrument for the benefit of the ruler, who should have no qualms at using whatever means are at his disposal to keep the citizenry suppressed. Unlike Plato and Aristotle, though, Machiavelli was not looking to describe the ideal society, merely to present a guide to getting and preserving power and the status quo.

His other major contribution to political thought, the "Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio" ("Discourses on Livy") was begun around 1516 and completed in 1518 or 1519. It was an exposition of the principles of republican rule, masquerading as a commentary on the work of the famous historian of the Roman Republic. It constitutes a series of lessons on how a republic should be started and structured, including the concept of checks and balances, the strength of a tripartite structure, and the superiority of a republic over a principality or monarchy. If not the first, then it was certainly the most important work on republicanism in the early modern period.

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|

|