Introduction | Life | Work | Books

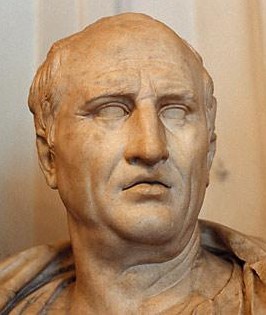

Marcus Tullius Cicero

(From a statue in Rome)

|

|

Marcus Tullius Cicero (usually known simply as Cicero) (106 - 43 B.C.) was a Roman philosopher, orator and statesman of the Roman period. He was a central political figure during the turbulent reign of Julius Caesar, and politics was always the most important thing in his life, but he still managed to produce six influential books on rhetoric and eight on philosophy (much of it during enforced periods of exile).

He is generally perceived to be one of the most versatile minds of ancient Rome, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists. While perhaps not an exceptional or original thinker, he was instrumental in introducing the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy, and was declared a “righteous pagan” by the early Catholic Church (meaning that many of his works were deemed worthy of preservation - St. Augustine and others quoted liberally from his works).

Cicero was born on 3 January 106 B.C. in Arpinum, a hill town south of Rome. His father was a well-to-do and well-read member of the semi-noble equestrian (or knight) class with good connections in Rome, although with no familial ties to the Roman patrician or senatorial class. Little is known about his mother, Helvia.

He was an extremely talented student, whose learning attracted attention from all over Rome, leading to an opportunity to study Roman law under the prominent politician and legal authority Quintus Mucius Scaevola (c. 159 - 88 B.C.). His fellow students with Scaevola were Gaius Marius Minor, Servius Sulpicius Rufus (106 - 43 B.C., who became a famous lawyer), and Titus Pomponius Atticus (c. 110 - 32 B.C., who became Cicero's closest friend, chief emotional support and adviser). Cicero also had the support of his family's patrons, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus (163 - 89 B.C.) and Lucius Licinius Crassus (140 -91 B.C., who was a model to Cicero both as an orator and as a statesman).

In the late 90's and early 80's B.C., Cicero fell in love with philosophy, which was to have a great role in his life. The first philosopher he met was the Epicurean philosopher Phaedrus (d. 70 B.C.), when he was visiting Rome in around 91 B.C. In 87 B.C., Philo of Larissa (c. 159 - 84 B.C.), then head of the New Academy in Athens, visited Rome and Cicero enthusiastically absorbed the philosophy of Academic Skepticism at his feet. Cicero also met Diodotus (d. 59 B.C.), a Stoic, and for a time he adopted a modified Stoicism, and Diodotus became Cicero's protégé and lived in his house until his death.

Cicero's ambitions for an illustrious career in public civil service started with some time in military service in 90 - 88 B.C. (although he had no taste for military life), and then the early years in his career as a lawyer around 83 - 81 B.C., including the politically courageous defense of Sextus Roscius on a charge of parricide. After winning this sensitive case, however, Cicero thought it prudent to leave Italy for a while and traveled to Athens to stay with his childhood friend, Atticus. There, he further consulted with philosophers of the Academy and the New Academy, and particularly with the rhetorician Apollonius Molon of Rhodes (fl. 70 B.C.) in order to learn a less exhausting style of public speaking.

On his return to Rome, Cicero's reputation rose very quickly. In 79 B.C., he married Terentia, a wealthy heiress of patrician background. The marriage, which was initially a marriage of convenience, was harmonious for over 30 years, until their divorce in 45 B.C., and they had two children, Tullia Ciceronis (b. 78 B.C.) and Marcus Tullius Cicero Minor (b. 65 B.C.) . He rose to the position of quaestor (a financial administrator, which also made him a member of the Roman Senate) for western Sicily in 75 B.C.. His career received a further fillip from the great success of his prosecution of Gaius Verres (120 - 43 B.C.), a corrupt governor of Sicily.

Despite his lack of social standing, he was able to ascend the Roman cursus honorum (sequence of public offices) and was made consulin 63 B.C., at the relatively young age of 43. After helping to suppress a conspiracy, however, he was forced into exile in Thessalonica, Greece in 58 B.C., although he was rehabilitated just a year later and his properties restored. When Julius Caesar (100 - 44 B.C.) invaded Italy in 49 B.C., Cicero, having thown in his lot with Caesar's main rival, Pompey (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus: 106 - 48 B.C.), again fled Rome, this time to Illyria (modern-day Albania). Caesar eventually pardoned him, but Cicero returned to Rome very cautiously.

Soon after his divorce from Terentia in 45 B.C., his daughter (and favorite) Tullia died, and for a long time Cicero was inconsolable. He was also saddened that his son Marcus insisted on pursuing a military career rather than philosophy, even if later Marcus rose to the position of proconsul of Syria and the province of Asia.

In the wake of Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 B.C., Cicero became a popular leader during the period of instability that followed, supporting Octavian (63 B.C. - 14 A.D.), Caesar's heir and adopted son (later to become Emperor Caesar Augustus). He orchestrated political attacks on Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius: 83 - 30 B.C.) who was jockeying for power and scheming to take revenge on Caesar's murderers. In reprisal, he was hunted down by Mark Antony's forces and was himself summarily assassinated on 7 December, 43 B.C. at Formia, between Rome and Naples.

Among 60 speeches (both as a lawyer and as a senator) and over 900 letters of Cicero which have been preserved, six influential books on rhetoric and eight on philosophy have come down to us (although some in fragmentary condition). Given that they were designed with a political purpose in mind, we cannot be sure of Cicero's actual opinions, and it should be noted that the dialogue form of many of them is useful for an author who wishes to express a number of opinions without having to endorse one.

In the political chaos following the dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138 - 78 B.C.), and the First Triumvirate (the unofficial political alliance of Julius Caesar, Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus), Cicero sought to reinstate (and, if possible, improve) what he thought of as the "golden age" of the Roman Republic, ruled by a selfless nobility of successful individuals. He also looked to boost the influence of his own family's equestrian class, rather than relying on the self-serving and often corrupt patrician class. His political vision is detailed in the "De Re Publica", of which unfortunately only fragments remain, including the famous Dream of Scipio.

He tried to use philosophy to bring about his political goals, which, in an age when serious philosophy was still very much centered in Greece, required making it accessible to a Roman audience through Latin translations of the major Greek works and summaries of the beliefs of the primary Greek philosophical schools of the time (Skepticism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism and Epicureanism). He was well acquainted with all these schools (he had teachers in each of them at different times of his life), and he is the source of much of our knowledge about these schools. He professed allegiance throughout his life to the Skepticism of the New Academy (which, as a politician and a lawyer, with the need to be able see as many sides of an argument as possible, is probably understandable).

See the additional sources and recommended reading list below, or check the philosophy books page for a full list. Whenever possible, I linked to books with my amazon affiliate code, and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Purchasing from these links helps to keep the website running, and I am grateful for your support!

|

|